Archive

“Very rare liquors”; Centuries Old Tasting Notes and A New One of Tenerife Wine

I am always on the look out for a wine from the Canary Islands but I rarely spot a bottle for they have not caught on in the Washington, DC market. This might be due to the slight premium in price, no doubt aided by the extra shipping logistics. I am willing to pay this premium because I find the flavors unique. Jancis Robinson wrote about these wines in her February article The Canaries – where vines, and wines, creep up on you. She even noted that Canary Island wines were “hugely popular in Britain in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries” as evidenced by their inclusion in Twelfth Night. But what was it that made those wines so popular?

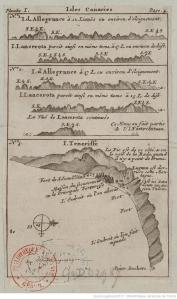

Isle Canaries. 1700-1799. Bibliothèque nationale de France, département Cartes et plans, GE DD-2987 (8476)

During the 17th century the most popular wine from the Canary Islands was the sweet, white Malmsey. John Paige was a London merchant who developed a trade during the 1640s and 1650s importing “luxury wine from Tenerife”.[1] Amazingly, his business letters with his trading associate William Clerke survived from the years 1648 to 1658. These letters provide fascinating details about the Canary wine trade. John Paige wrote on May 28, 1649, that of the 11 pipes he received the “Rambla wines proved white and green, but the Orotava wines proved the richest Canaries that ever came to England”.[2] In a previous letter he noted the Orotava vintage was “extraordinary rich but high colour.” Unfortunately the vintners were afraid to purchase them because they believed they had “put molasses in them and that they were not natural from the grape.” John Paige continued to his agent that “now our vintners are grown so curious in their tastes that none but rare wines will serve their terms.” He noted the price difference “betwixt ordinary and very good wines ” exceeded “£4 or £5 per pipe.” That is a significant difference given that he had sold the 11 pipes at £20 5s ready money. One well received parcel was later described as containing “gallant rich wines”.[3] Two years later John Paige wrote that the wines of Mr. Rouse and Mr. Audley respectively sold for £27 and £29 per pipe. This was a suitable price given that “they were the best wines” he had ever tasted.

Not every wine that John Paige imported was well received. On January 8, 1652, he noted that other merchants were selling at £29 and £30 per pipe. He struggled to sell his wine at £18 per pipe for “no man’s prove [so bad as] mine, insomuch that no man will taste them.”[4] We may guess what these unfavorable wines tasted like based on other comment by John Paige. These bad wines were “generally green”, “small, hungry wines”, and even “mean wines, green and thin bodies and flashy” [5] Even “better bodied wines…were bad enough both, being very green”.[6] When John Paige could not sell merchandise he wrote of the “goods here are drugs, no vent at all for them”.[7] He received bad wine from William Clerke on a number of occasions writing him that “You are not fully sensible” for the good wines were “a precious commodity” and “bad wines as great a drug.”

Today, it is the dry, red wines that I look for. In Jancis Robinson’s article she comments that “most interesting was a visit to the painstakingly assembled” vineyards of Suertes del Marqués. Just a few days ago Jenn and I tasted the introductory blend from this estate, the 2012 Suertes del Marqués, 7 Fuentes, Valle de La Orotava, Tenerife. I was immediately drawn in by the exotically spiced nose that echoed through in the flavors. It really was curious. This wine was purchased at the Wine Source in Baltimore.

2012 Suertes del Marqués, 7 Fuentes, Valle de La Orotava, Tenerife – $20

Imported by Eric Solomon European Cellars Selections. This wine is a blend of 98% Listan Negra and 2% Tintilla sourced from 10-100 year old vines from three parcels located at 400-650 meters. The fruit was separately fermented in stainless steel then aged for eight months in concrete and French oak casks. Alcohol 13%. The nose bore exotic aromas of scented red berries. In the mouth the red fruit had mineral undertones and was enlivened by a lot of acidity that made way to a spicy finish. There were tightly-ripe raspberry flavors, minerals, and a dry finish. The persistent aftertaste carried finely ripe flavors. *** Now-2017.

[1] ‘Introduction’, The letters of John Paige, London merchant, 1648-58: London Record Society 21 (1984), pp. IX-XXXIX. URL: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=63981&strquery=canary wine Date accessed: 18 July 2014.

[2]’Letters: 1649′, The letters of John Paige, London merchant, 1648-58: London Record Society 21 (1984), pp. 1-8. URL: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=63983&strquery=taste Date accessed: 18 July 2014.

[3] ‘Letters: 1650’, The letters of John Paige, London merchant, 1648-58: London Record Society 21 (1984), pp. 8-31. URL: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=63984&strquery=rich Date accessed: 18 July 2014.

[4] ‘Letters: 1652’, The letters of John Paige, London merchant, 1648-58: London Record Society 21 (1984), pp. 57-82. URL: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=63986&strquery=taste Date accessed: 18 July 2014.

[5] ‘Letters: 1653’, The letters of John Paige, London merchant, 1648-58: London Record Society 21 (1984), pp. 82-99. URL: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=63987&strquery=mean Date accessed: 18 July 2014.

[6] ‘Letters: 1651’, The letters of John Paige, London merchant, 1648-58: London Record Society 21 (1984), pp. 31-57. URL: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=63985&strquery=very green Date accessed: 18 July 2014.

[7] ‘Letters: 1651’, The letters of John Paige, London merchant, 1648-58: London Record Society 21 (1984), pp. 31-57. URL: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=63985&strquery=drug Date accessed: 18 July 2014.

“Planted Among the Rocks” : Thomas Nichols 16th Century Descriptions of the Wines of the Canary Islands

Perhaps I am naïve but I continue to be amazed by the vinous materials available through online archives. Even well-known primary sources reveal additional details rarely or not at all discussed. In searching for additional sources to add to my upcoming Wine and the Sea post I came across some fascinating descriptions related to the wines of the Canary Islands. The English trade with the Canary Islands clearly existed in the 16th century when the sweet white Malvasia grew became popular in Europe. As I noted in A Brief History of Wine from the Canary Islands there were vineyards in in Tenerife, Gran Canaria, and Las Palmas. In Richard Hakluyt’s The principal nauigations, voyages, traffiques and discoueries of the English nation made by sea or ouer-land, to the remote and farthest distant quarters of the earth, at any time within the compasse of these 1600. Yeres (1599-1600) there is a description of the Canary Islands written by the Englishman Thomas Nichols.[1]

Hakluyt, Richard. The Principal Navigations, Voyages, Traffiques, and Discoveries. 1599.

Thomas Nichols was born in the city of Gloucester in 1532.[2] In 1557 he moved to Tenerife where he was a commercial representative for three London merchants for seven years. In 1583 he published A Pleasant Description of the Fortunate Ilandes, Called the Islands of Canaria, with Their Straunge Fruits and Commodities.[3] Of Gran Canaria, Thomas Nichols writes that it had “singular good wine, especially in the towne of Telde.” Of Tenerife were there was “very good wines in abundance…Out of this Iland is laden great quantity of wines for the West India, and other countreys. The best growth on a hill side called the Ramble.” The Island of La Gomera had “great plenty of wine.” The Island of La Palma was “fruitfull of wine” with the city of Palma showing a “great concentration for wines, which are laden for the West India & other places.” The best location for vines “grow in a soile called the Brenia, where yerely is gathered twelue thousand buts of wine like vnto Malmsies.” Of the islands of Lanzarota and Forteuentura where there was “very little wine of the growth of those Ilands.”

A particularly interesting entry appears for El Hierro or “The Iland of Yron” where “There is no wine in all that Island, but onely one vineyard that an English man of Taunton in the West country planted among rocks, his name was John Hill.” Perhaps this is the John Hill (1529-1611) who was born in Houndstone, Somerset and married Jane Rodney in 1569. What is fascinating is that we know an Englishman was cultivating a vineyard in the Canary Islands sometime between 1557 and 1564. These facts are not entirely new but the Google entry for the El Hierro (DO), as well as a few others, incorrectly dates John Hill’s vineyard to the 17th century.[4]

The Medical Use of Canary Wine in 17th Century England

Introduction

Canary Island wines were not just popular for their taste but also for their medicinal value. In addition to their use by Dr. Thomas Sydenham in London their medical use is documented in such countries as France by the early pioneer in geriatrics Francois Ranchin, “Talia autem funt canarium album spirituosum admodum & substantisicum vinum maluaticum…”. Very much like their popularity as a beverage Canary wine was medically used through the 19th century. In fact the wines of Tenerife were the official wine used by the U.S. Pharmacopeia. For in the early 19th century there was little American wine made, with the best grown on the banks of the Ohio River in Vevey, Indiana. To expand on my previous post on A Brief History of Wine from the Canary Islands I shall focus on the medical uses of Canary Island wines in 17th century London.

Medical history is a complex subject which I find fascinating and I hope that this post on the medical use of Canary Wine might expose you to an alternative history of wine. I have spent my New Year’s vacation researching original medical texts and cramming on medical history. Most of what I present here is not new and I must admit it is presented in a unimaginative chronological format. However this blog inherently reflects the chronology of the wines I tasted and subjects which interest me. In that light I see this post as a starting point fo future posts. For others you will find many references which you may spend many hours happily reading.

A Brief Introduction to English Medicine in the 17th Century

In 1600 London was the largest city in England having a population of 200,000. Mortality rates were high and the average life expectancy in a better parish of central London was only 35 years of age. There were many diseases in London such as dysentery, typhoid, and salmonella along with the plagues of 1603, 1625, and 1665. A typical sick person often treated themselves or relied on a family member. Medical lay knowledge was widespread with clergymen and their wives often treating the sick. A wealthy person could hire a Physician for diagnosis and advice. Physicians were considered at the top level of the medical hierarchy having attended university, possessing a gentlemanly bearing, and being a member of the College of Physicians. Beneath the physicians were the surgeons for they used their hands to cure patients. They trained by apprenticeship and could handle external issues, setting of bones, and some internal operations. Parallel to the Surgeons were the Apothecary’s who dispensed medicines prescribed by the surgeons. Finally there were the quacks and mountebanks who could purchase the privilege to practice their own form of medicine.

London’s large population ensured a sizeable number of physicians and surgeons. In 1600 it is estimated that there were 50 members in the College of Physicians, 100 surgeons, 100 apothecaries, and 250 unlicensed practitioners. The College of Physicians of London was created in 1518 to admit members through examination, the Barber-Surgeon’s Company was created in 1540 licensing through apprenticeship and examination, and the Society of Apothecaries was created in 1617. Medical knowledge was typically communicated through texts particularly those of Galen. Between 1486 and 1604 some 193 different vernacular medical works were published in England. In the 16th and 17th centuries most books published in England were written in English and not in Latin. These books ranged from remedy books for the literate population to textbooks written specifically for physicians. Between 1640 and 1660 some 238 medical books in England. This increase in the availability of medical knowledge followed a trend of increased literacy and demand by the middle and upper classes for accessible medical knowledge.

The Medical Texts

There are a great number of 17th century English medical texts which are readily accessible for research. I have relied on Google Books to provide quotes from these medical texts. I have tried to preserve the actual spelling and formatting. Any mistakes are solely my own.

The Canary Islands were first known for exporting sugar. As an aside, while Canary sugarcane is mentioned in John Daniels Mylius’ Opus Medico-Chymicum, 1620 I found no references to Canary sugarcane in the English medical texts. For Canary wine I have chosen texts by physicians, surgeons, and empirics to illustrate the various uses of the wine. The introduction of Canary wine in English medicine seems to track the general popularity as a drink. During the 1660s and 1670s Canary wine was one of the most expensive wines available. The maximum prices charged for claret were 6d. per pint, Rhenish 9d. per pint, sack 11d. per pint, and Canary 12d. per pint. This price may be reflected in the infrequent use of Canary wine in a remedy. Though it is found in medical texts by all sorts of practitioners it often only appears in a few remedies. It was drunk alone as part of a regular prevantative diet. In compound remedies there is at least one mention of boiling the ingredients with the wine but it appears to typically have ingredients steeped in it or as a cordial for drops of the actual remedy to be put in.

In 1618, one year after the Society of Apothecaries was created, the College of Physicians published the first Pharmacopeia in London. This text ensured that compound remedies were made using a standard set of ingredients. Under the Vina Medicata section there are four remedies listed: Vinum Benedictum, Vinum Chalybeatum, Vinum Scilliticum, and Vinum Viperinum. Though the catalog of ingredients simply list vinum the description of the remedy is more specific Vini albi Hispanici or Spanish White Wine. From what I can gather the College of Physicians does not include the use of Canary wine until the 18th century when they published their New Pharmacopoeia.

VINUM BENEDICTUM

Croci Metallorum pulv. unciam imam. Vini albi Hispanici feíquilibram Macerentur. Colac.Pharmacopoeia Collegii Regalis Medicorum Londinensis. 1618.

It is not until 1638 that I found a medical reference to Canary wine. Though only two decades later the amount of Canary wine taxed at London rose from an 10 year average of 1774 pipes in 1619 to 5,033 pipes in 1633. James Howell remarked in 1634, “I think there’s more Canary brought into England than into all the World besides….they go down everyone’s throat both young and old, like milk.” Perhaps this popularity led Alexander Read, Doctor of Physick to include it in his remedy for Syncope. Throughout his text he references the use of wine, white wine, red wine, astringent red wine, strong wine, spirit of wine, and claret (for cleaning a wound of extraneous bodies). But only for Syncope does he specifically recommend Allicante, Malmsey, Canary Wine, or White Bastard.

Syncope

Syncope then is a sudden decay or abolition of the strength of the body, according to Galen, 12 method, c 5 As lipotlbymia is only an imminution of the same: the part affected the heart.

Internall meanes.

As for the internall meanes, a Sop in strong wine, as alligant, malmesee, canary wine, or white bastard is very good, so that the wine be drunke together with the toast. Confectio alkermes dissolved in cinamome water, or treacle dissolved in aqua celesiis and ministred are effectuall.Read, Alexander. A treatise of the first part of chirugerie. 1638

These first two books were intended for professional physicians and surgeons. In 1656 The Skilful Physician was published for the general public. It instructed how to maintain good health through diet and if that failed then a comprehensive list of remedies is provided. An entire section is devoted to wine featuring 58 recipes. In the list of ingredients we find such specific wines as: Allegant, Bastard, Batew, Claret, Deal, Graves, Hollocks, Malaga, Malmsey, Muskadine, and Sack. There is but one remedy involving Canary wine and that is for dropsie.

DROPSIE

A very good Drink to cure the Dropsie.

Take of Peperitis Roots, otherwise called Horse Rhadish, three ounces, slice them by the length very thin, of Licoras scarped and bruised two ounces, Winter Savory, Time, Peniroyal, the tops of Nettles of each a small handful; of Smallage roots, Fennel roots, of each one ounce, of sweet Fennel seeds bruised three ounces, infuse all these things one night in two quarts of fairwater, and three pints of Canary Wine, then boil all together the next day one quarter of an hour, then take it from the fire and let it run through a clean cloth and so drink a small draught thereof in the morning fasting, and as much in the afternoon at three a clock and fast two hours after it, and so continue taking it until you be wel. Mr. Smart.Deodate. The Skilful Physician. 1656.

In the diary of Samuel Pepys there is a unique reference to Canary wine. In a letter dated July 2nd, 1664 we find, “Dr. Burnett’s adivce to mee. Old Canary or Malaga wine you may drinke to three or 4 glasses, but noe new wine, and what wine you drinke, lett it bee at meales.” This is the only reference to “Old Canary” wine. The most famous medical book for the general public was Nicolas Culpeper’s English Physitian. Though published prior to The Skilful Physician I have only been able to access The English Physitian Enlarged which was published in 1666. There are hundreds of references to wine but only a handful for specific wines. In fact I only came across four references to Claret wine and one for Canary wine.

Rest-Harrow, or Cammoak.

Government and Vertues. It is under the Dominion of Mars, It is singular good to provoke Urin when it is stopped, and to break and drive forth the stone, which the Powder of the Bark of the root taken in Wine performeth effectually.

Balneo Marie with four pound of the Root hereof first sliced small, and afterwards steeped in a gallon of Canary Wine, is singular good for all the purposes aforesaid, and to cleanse the passages of the Urin.Culpeper, Nicolas. The English Physitian Enlarged. 1666.

The popularity of Canary wine continued to grow from a post Plague 1665 and Great Fire 1666 level of 5500 pipes imported into London to a high of 6700 pipes in 1687. These are ten year averages which hide such peaks as 9210 pipes in 1681. It is during this period that Dr. Thomas Sydenham publishes his recipe for Laudanum which uses Canary wine. Dr. Sydenham employed a variety of wines such as Claret, French, Malaga, Rhenish, Sack, and Spanish. Towards the end of the 17th century increased consumer spending lead to an increase in medicines and texts from empirics. Dr. Thomas Willis attempted to provide a rational explanation on the operation of remedies in the body. He preferred chemical remedies in which he used Florence, Malaga, Rhenish, Spanish, and White wine. Canary wine was featured in several remedies including that for Consumption of the Lungs.

Instrctions and Prescripts for the Cure of the Phythisick, and Consumption of the Lungs.

5. Balsams.

Take Artificial distill’d Balsam, commonly call’d Mother of Balsam two Drams: The Dose is from Six Drops to ten, in a spoonful of Syrup of Violets, or of Canary Wine at Night, and in the Morning.

10.

In a Constitution that is not hot, especially if there be no fervent heat of the Blood or Praecordia, to six or seven Pounds of Milk add of Canary Wine a Pound or two, and in a Phlegmatick or Aged Body, instead of Milk,, let the Mestruum be Ale or Brunswick Beer.

Willis. The London Practice of Physick. 1685.

At the peak of the Canary wine imports we find it being used in other chemical remedies.

Of MERCURY, or Quick-silver

The Sweet Oyl of Mercury.

…; Prevalent in the Distempers of Venus, Dropsies, Quartans, &c. The Dose is from four to six drops in Canary, Conserves, or Syrups, every other day, until a perfect Cure.Y-Worth, W. Chymicus Rationalis: or, The Fundamental Grounds of the Chymical Art. 1692.

References

If I were to pick one reference to recommend it is Andrew Wear’s Knowledge & Practice in English Medicine, 1550-1680. It is this book which has placed a medical structure to the history of Canary wine.

Deodate. The Skilful Physician. Tho. Macey, London 1656

Culpeper, Nicolas. The English Physitian Enlarged. John Streater, London, 1666.

Hori, Motoko. “The Price and Quality of Wine and Conspicuous Consumption in England 1646-1759”, English Historical Review, Vol 73 N0. 505, 2008.

Mylius, Johann Daniel. Opus Medico-Chymicum. Frankfurt, 1620.

Pechey, John. The Whole Works Of that Excellent Practical Physician, Dr. Thomas Sydenham. 9th Edition, J. Darby, London 1729.

Physicians, College of. Pharmacopoeia Collegii Regalis Medicorum Londinensis. Typis G. Bowyer, Londini, MDCCXXI, 1721

Ranchin, Francois. Opuscula medica utili, iocundaque rerum varietate referta. 1627

Read, Alexander. A treatise of the first part of chirugerie. John Haviland, London 1638.

Steckley, George F. “The Wine Economy of Tenerife in the Seventeenth Century”, The Economic History Review, Vol. 33, No. 3, 1980.

Thacher, James. The American new dispensatory. T.B. Wait and Co, Boston, 1810.

Wear, Andrew. Knowledge & Practice in English Medicine, 1550-1680. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2000.

Wear, Andrew. Medicine in Society, Historical Essays. Cambirdge University Press, Cambridge, 1994.

Wheatley, Henry B. The diary of Samuel Pepys. George E. Croscup, New York 1894.

Willis. The London Practice of Physick. Thomas Basset, London, 1685.

Wood, George B. The Dispensatory of the United States of America. Grigg & Elliot, Philadelphia, 1833.

Y-Worth, W. Chymicus Rationalis: or, The Fundamental Grounds of the Chymical Art. Thomas Salusbury, London, 1692.

A Brief History of Wine from the Canary Islands

Wines have been exported from the Canary Islands since the late 16th century. Even a quick look into the history of wine will reveal widespread and common reference to Canary wine. As popular as it was it eventually experienced a decline in exports such that many readers of this blog may not have tasted an example. Indeed as broad as I drink I did not taste my first sip of Canary wine until this month. From what I gather the resurgence of Canary Island wine in the United States is owed to the importer Jose Pastor. The Canary Islands represent the largest regional share in his portfolio with 14 out of 45 producers listed on the website. Jose imported his first Canary Island wine back in 2007. Since then this part of his portfolio appears to have gained traction in San Francisco and New York City. During my recent trip to New York City one of the first questions I was asked at both Despana Vinos y Mas and Chambers Street Wines was whether I had tried one of the island wines. I had not so I walked away with three different wines. My knowledge of the Canary Island wines was spotted at best so for my next several posts I will focus on the turbulent and fascinating history of Canary wine and my actual tasting notes.

The Origins of Canary Wine

The Canary Islands along with Madeira were discovered by the Portuguese and Castilians in the 15th century. By the end of the 15th century it was agreed that the Castillians would control the Canary Islands and the Portuguese would control Madeira. The Canary Islands are located off of the coast of Africa and were an important port of call before ships left for the Americas. Land was cheap so plantations were quickly created to grow and mill sugar for export. The rise of Brazilian and Caribbean sugar exports to Europe eventually undermined the Canary and Madeiran sugar exports. Vineyard were also planted on the islands with exports of sweet white Malvasia from Tenerife gaining popularity in Europe throughout the 16th century. By the mid 17th century West Indian sugar was half the cost of Canarian. With the decline of sugar production and the rise in price of wine, vineyards were greatly expanded. The main varietal was Malvasia brought over from Cyprus. Its popularity resulted in a vineyard expansion to such extent that grain needed to be imported to the islands.

There were three main markets for Canary wine: Spanish and Portuguese provinces in America, Portuguese Cape Verde, and European markets in France, the Netherlands, and England. To these markets three types of wine were exported the highly popular Malmsey produced from Malvasia, a greenish dry wine, and a purplish sweet wine produced from late harvested grapes. Though the vineyards were located in Teneriffe, Gran Canaria, and Las Palmas that vast majority were located in Tenerife. In 1600 Tenerife account for 62% of the total taxes on trade in the Canary Islands and by 1688 it account for 90%.

War with Spain ended in 1604 and the Canary wine trade developed. By the mid seventeenth century Portuguese independence from Spain meant the majority of Canary wine was exported to England. The price of Canary wine in the early 1660s had reached twice that as in 1640. Meetings were held to fix the price of Canary wine at 29 Pounds per Butt in 1662 and 32 Pounds per Butt in 1664. With such high prices a group of merchants received a royal patent from Charles II in 1665 to form the Governour and Company of Merchants trading to the Canary Island. Also known as The Canary Company the goal was to restrict the Canary Island wine import business to the Company so that they could negotiate for lower wine prices. This was not received well at the Canary Islands where the Company’s agents were expelled from Teneriffe in 1666. In an attempt to overthrow the Company, English ships were no longer allowed to land and no English merchants were allowed to live on the Islands until the Company’s charter was recalled. In response the importation of Canary wine to England was banned.

During these very same years London experienced the great fire of 1666 and the Dutch Navy were wearing on British ships. With the great losses due to the fire and difficulties in transportation within London and over the seas, there were extensive challenges to importation and sales. In London, members of the Company sought to petition alterations to the patent which ultimately lead to the cancellation of the patent in 1667 and the renewal of free trade with the Canary Islands. Just one year later Charlie II married Catherine of Braganza, a Portuguese princess. He subsequently banned the importation of Canary wines to the benefit of Portuguese wines. Trade eventually resumed, in 1681 4.5 millon quart bottles or 4,464 pipes of Canary wine were taxed in London. By the 1690s two-thirds of the Malvasia from Tenerife was imported into London alone. Rising import duties began to reduce the profitability of the Canary wine trade. The War of the Spanish Succession broke out in 1701 forcing English merchants to once again leave Tenerife.

Canary Wines and Medicine

Canary Wine was not just consumed but prescribed in medicine. Dr. Thomas Sydenham (1624-1689) revived the Hippocratic methods of observation and was a founder of epidemiology. He considered the foundation of medicine to be rooted in beside experiences. As such he actively studied epidemics in London beginning in the 1650s. He is famous for the introduction of Cinchona bark and his use of laudanum which reintroduced it to the medical community. In 1676 he published Medical Observations Concerning the History and Cure of Acute Diseases. In it we find his recipe for Laudanum.

Strained opium (2oz), saffron (1oz), cinnamon & cloves (1 drachm each), & Canary wine (1 pint)

As to his use of Canary wine we may find reason in his remedy to the symptoms of the Gout.

I have tried many things for the Fits of the last Tears to lessen this Symptom but nothing did so much good as a small draught of Canary Wine taken now and then when the Sickness and Faintness afflict the Sick Nor is Red French Wine or Venice Treacle or any other Cordial thing which I have yet known so effectual But we must imagine that neither this Wine or any other Cordial if Exercise be not used can wholly preserve the Patient.

Canary Wine is used throughout his Medical Observations including a method to invigorate and strengthen the blood in the case of diabetes.

Take of the Roots of Elecampane Masterwort, Angelica, and Gentian each half an Ounce; of the Leaves of Roman Wormwood; white Horehound; of the lesser Centaury and of Calaminth, each one Handful of Juniper-berries one Ounce : Let them be cut small and infused in five Pints of Canary, let them stand together in a cold Infusion, and strain it as you use it.

Canary Wines in Bristol

I spent my formative year of wine-drinking in Bristol, England. It was a fantastic city to buy wine in, with both new and long-established wine merchants. I often shopped at Averys founded in 1793 and John Harvey & sons founded in 1796. Starting in the 15th century Bristol was the second most important port after London. If we look at the 1620s and 1630s we see that this extended to wine imports with London importing an average of 19,650 tuns seconded by Bristol at 2,341 tuns.

There are a large variety of records related to the importation of wine into Britain. They frequently refer to wine in terms of tuns, pipes, and hogsheads. A tun is an English unit of liquid volume originally set at 256 gallons then reduced to 252 wine gallons by the 15th century and eventually 210 Imperial gallons in 1826. A pipe or butt is half the volume of a tun and a hogshead is a quarter the volume of a tun.

Import statistics rely on various customs books. They reflect the variation in harvest date and yield, alignment with the bookkeeping calendar, and also greater political events. In looking at 17th century importation volume of Canary wine to some degree they reflect the War with Spain in 1625-1630 and the war with France in 1627 which made 1620 into very early 1630s a difficult time. This was followed by extra taxes on wine in the 1630s and a privileges granted to London wine merchants. The decline in wine imports continued with the Civil War 1640-1641 and took until the 1680s to recover. By then higher duties were being imposed. With higher wine prices and the availability of alternative beverages wine imports declined again in the late 17th century.

Canary Wine Imports at Bristol

Sept 1600 – Sept 1601 1 – Canary wine 108 tuns (5.8%) out of 1871.5 tuns.

Dec 1612 – Dec 1613 2 – Canary wine 196 pipes (98 tuns, 5.0%) out of 1942 tuns.

Dec 1624 – Dec 1625 3 – Canary wine 171 pipes (85.5 tuns, 4.8% ) out of 1790 tuns.

Sept 1654- Sept 1655 6 – Canary wine 33 pipes and 10 quarter casks (19 tuns, 2.6%) out of 726 tuns.

Sept 1682 – Sept 1683 11 – Canary wine 15.5 pipes(7.25 tuns, 0.6%) out of 1206 tuns.

Sept 1685 – Sept 1686 12 – Canary wine 78 pipes (39 tuns, 4.8%) out of 813 tuns.Based on Port Books and Society of Merchant Venturers Wharfage Books

In the 17th century Canary wine imports by volume peaked in 1600-1601 at 108 tuns. Wine was typically consumed in one quart bottle units so this volume represents some 108,864 bottles worth of Canary wine. The population of Bristol was approximately 10,000-11,000 during the first decade of the 17th century. Certainly not all of the wine was consumed within Bristol but if it was this represents 10 bottles for every man, woman, and child for one year alone.

Canary Wines in the County of Suffolk

At a more individual scale we can look at the consumption of Canary wine by John Hervey, 1st Earl of Bristol. John Hervey (1665-1751) became a member of Parliament in 1694 then became the 1st Baron Hervey of Ickworth in the County of Suffolk in 1703 and finally the 1st Earl of Bristol in 1714. While his diary is sparse with entries his Expensive Book are particularly detailed with expenditures on wine. The first recorded year of wine expenditures is 1689 when he bought Clarrett and Duncomb wine. In 1690 he began to drink Hermitage and in 1697 he purchased his first pipe of Canary wine. John Hervey drank diversely and well. In 1702 he purchased 4 hogshead of “obrian” (Chateau Haut-Brion) and in 1703 he purchased one hogshead of “Margoose Clarett” (Chateau Margaux). Over the span of 54 year he purchased Canary wine ten times for a total volume around 2 tuns. This represents an approximate household consumption of 2,106 quart bottle or three bottles per month. The cost of his Canary wine ranged from 30 Pounds per pipe all the way up to 100 Pounds per pipe. In the absence of an established annual trend this may reflect a range in quality of the Canary wine purchased.

Wine Expenses from The Diary of John Hervey covering 1688-1742

June 18 1697, 80 Pounds for 2 pipes of Fayall & 1 Pipe of Canary.

June 21 1697, Parcell of pictures & for a hogshead of old Canary, 80 Pounds.

Jan 15 1705, 9 gallons 1 quart of Canary he bought for me 4..15..0.

Feb 17 1710, 4th part of a pipe of Canary, 15 Pounds.

Feb 7 1711 60 gallons of Palme & Canary wine etc. 33..10..0.

March 8, 1718, 30 gallons of Canary, 12..1..6.

March 21 1718, Port-wines, Canary, & all other demands to this day, 114..17..6.

Jan 10 1724, 3 parcells of Canary, a pipe of Porte at 28 Pounds.

March 29 1734, for a pipe of Canary 30 Pounds.

Mar 26 1741, a hogshead of Canary at 31..10..0.

Canary Wine in the 18th and 19th Centuries

Geographical Distribution Of Indigenous Vegetation, Arthur Henfrey, Edinburgh,1854, Image from David Rumsey Map Collection

The Canary Island wine trade with Britain never recovered the vigor of the 17th century. At the beginning of the 18th century English imports of Portuguese wines, including port wine, and the wines of Madeira increased due to favorable relationships between Britain and Portugal. Thus with the Canary wine we see that in 1785 only 65 tuns were imported into Britain, in 1808 it increased to 1683 tuns, and by 1821 it was down to 1000 tuns. Though exports from the Canary islands to Britain decreased the wines were still exported around the world. In Williamsburg, Virginia we find 22 bottles of Canary listed in the Inventory of the Estate of Joh Marott in 1717. Canary wines were also advertised for sale in The Virginia Gazette in 1771.

”To be SOLD at John Greenhow’s Store, near the Church, in Williamsburg, for ready Money, on reasonable Terms,…Old Spirits, best and common Arrack, Madeira, Lisbon, red port, Claret, Canary, and Renish Wines…”, Publisher: Purdie & dixon, Page: 3, Column: 2, 1771-12-12.

The 19th century view of Canary wine appears somewhat consistent in that Tenerife produced the largest amount of wine followed by Gran Canaria. Of the three wines produced the sweet Malmsey from Malvasia was considered the best. In 1833 Cyrus Redding published a book on wine commenting that the Canaries produce 25,000 pipes of white wine annually while 15,000 are consumed internally or distilled. Tenerife alone producing 22,000 pipes. Upon tasting a 126 year old bottle in a small pint-size bottle he found it was “flavour was good, and it had ample body.” “Teneriffe produces the best wines of all the islands, having the greatest body.” “On the eastern side of Palma, Malvasia, or Malmsey, is grown, which in a few years gains a bouquet like a ripe pine-apple. The dry wines are not as good as those of the other islands. The best vines do not grow more than a mile from the sea.”

In 1863 Agoston Haraszthy found the Canary Islands producing a large quantity of wine with Tenerife alone responsible for 40,000 pipes of wine. This included the Malvasia wine which he found “of agreeable taste, sweet and spirituous” and the “Vidogne, which though keen and tart when new, gains by age.” He notes the wines of Palma island were considered inferior. Two years later wine merchant W. R. Loftus states the principal islands were Gran Canaria and Tenerife. The wines also known as Teneriffe “resemble Madeira, though far from possessing its flavour or body.” The dry Vidonia produced from the Vidogna grape “has a good body, and improves with age. It is made from grapes gathered before they are ripened, and when new it is far from pleasant; but a few years soon removes this flavour, and greatly increases its mildness.” Palma is inferior to that of Teneriffe. The Malmsey is “very excellent, although possessing, as some affirm, an acid quality.” He notes that in 1827 417,703 gallons of Canary Wines were imported into Great Britain but have decreased ever since.

Though Agoston Haraszthy and W. R. Loftus do not mention the Powdery Mildew which hit the Canary Islands in 1852, Thomas George Shaw comments that the Oidium attack “sufferings and losses have been consequently great…”. The Canary Islands suffered two blows from Powdery Mildew in 1852 and Mildew in 1878. These attacks devastated the vineyards to such an extent that in 1888 Charles Edwards writes that he no longer purchased the wines for the disease “came disastrously upon the vineyards of Tenerife.” By the end of the 19th century the wine industry appears to have recovered. In 1898 A. Samler Brown wrote that wine exports reached a low of 4,855 Pounds in 1885 but just 13 years later had reached some 25,000 Pounds per year. The grapes planted were Tentillo, Negra Molle, Moscatel (black and white), Verdelho, Pedro Jimenez, Forastero, and Vija-Riega. The inferior vineyards were found higher up on the hills and were more susceptible to disease. The better vineyards were lower, warmer, and produced more expensive wines. Wines in barrel were mature in eight years but improved up to 25 years of age. Fortified wine was still produced along with a small amount of high quality sweet wine known as Gloria. Red Canary was also produced and Samler Brown found that the red wines of Tacoronte were the best reds in Tenerife. Indeed 90 years later Tacoronte-Acentejo became the first Denominacion de Origen (DO) in the Canary Islands.

Contemporary History

I have not found much detail on the 20th century history of Canary wine. In 1972 D. E. Pohren write, “the island of Tenerife, with its strong, dry white wine from Guimar, its heavy-bodied, strong red from Tacoronte, its aged wines from Icod, etc.; and La Palma, with its claret of 14-16% from Fuencaliente and its highly aromatic , white wine from localities scattered throughout the island”. In terms of varietals planted there are “Malvasia, pedro ximenez, albillo and listan predominate on the islands.” In 1992 Tacoronte-Acentejo on Tenerife was granted the first DO for the Canary Islands. Since then a total of 10 DOs have been granted, five of which on Tenerife with the remaining five on La Palma, Hierro, Gran Canaria, La Gomera, and Lanzarote. This year Decanter Magazine found the wines to have increased by 72.9% in volume and 5.4% in value, and the Balearic Islands, up 20.9% and 5.1% since 2011.

References

Brown, A. Samler. Madeira and the Canary Islands, 5th Edition. Sampson Low, Marsteon & Co, London 1898.

Edwards, Charles. Rise and Studies in the Canary Islands. T. Fisher Unwin, London, 1888.

Gray, Todd. From Tutor and Stuart Devon. University of Exeter Press, Exeter, 1992.

Haraszthy, Agoston. Grape Culture, Wines, and Wine-making. 1863.

Latimer, John. The Annals of Bristol In the Seventeenth Century. William George’s Sons, Bristol 1900.

Loftus, W. R. The Wine Merchant. George Burns Steam Printer, London, 1865.

McGrath, Patrick. Merchants and Merchandise in Seventeenth-Century Bristol, Volume XIX. J. W. Arrowsmith Ltd, Bristol, 1955.

Pechey, John. The Whole Works Of that Excellent Practical Physician, Dr. Thomas Sydenham. 9th Edition, J. Darby, London 1729.

Pohren, D. E. Adventures in Taste: The Wines and Folk Food of Spain. Artes Graficas Luis Perez, Madrid, 1972.

Redding, Cyrus. A History and Description of Modern Wines. Whittake, Treacher, & Arnot, London 1833.

Shaw, Thomas George. Wine, the Vine, and the Cellar. Spottiswood and Co., London, 1864.

Simon, Andre L. The History of the Wine Trade in England, Volume II. Wyman & Sons, London 1907.

Skeel, Caroline A. J. “The Canary Company”, The English Historical Review, No CXXIV. 1916.

Steckley, George F. “The Wine Economy of Tenerife in the Seventeenth Century”, The Economic History Review, Vol. 33, No. 3, 1980.

Unwin, Tim. Wine and the Vine. Routledge, New York, 1996.